Alexander Pushkin

Born: Moscow - 6 June 1799

Died: St. Petersburg - 10 February 1837

While, for the rest of the world, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky may vie for the position of Russia's greatest writer, among Russian speakers that honour belongs unquestionably to Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, the prolific Romantic poet who, before his untimely death at the age of 37, almost single-handedly conjured into being one of the world's greatest literary traditions.

Pushkin was both Russia's Byron and Russia's Shakespeare. His desperately romantic life - a series of ill-fated love affairs, clashes with authority, and a series of duels including his final, fatal encounter with the French cavalry officer George d'Anthès - and the lyric verse it inspired remain a potent primer to the classics for generation after generation of Russian school kids.

His affinity to Shakespeare is firstly in his position as the great profane humanist of Russian letters, his copious literary output ranging over almost every aspect of the human condition and always imbued by a broad philosophy that weighed ideas and ethics against individual experience and humour. Secondly, and more significantly still, it is in his unparalleled contribution to the codification of the Russian language. Not only has Pushkin provided educated Russians to this day with apt quotations for almost any situation, he also near single-handedly established Russian as a modern literary language, developing a vast number of previously unexplored literary forms and adding an unprecedented number of new words to the language.

Pushkin was born into an ancient but relatively obscure noble family in Moscow. His most famous ancestor was his maternal great grandfather Abram Petrovich Gannibal, the African slave whom Peter the Great made part of his household and later ennobled (Pushkin presented a fictionalized version of his life in the unfinished historical novel Peter the Great's Negro). In 1811, Pushkin joined the first intake of the Imperial Lyceum in Tsarskoye Selo, founded that year by Emperor Alexander I as a training ground for future statesmen. Here Pushkin enjoyed a superb liberal education and rapidly developed his poetic skills, publishing his first verses at the age of fifteen. By the time of his graduation in 1817, his poetry had already won the attention of St. Petersburg's leading literary circles.

Pushkin entered government service in the Collegium of Foreign Affairs but, given the pace of his creative output and his whirlwind social life, he had little time to devote to his government career. Even in his schooldays, Pushkin was drawn to the more liberal and free-thinking extremes of Petersburg's intelligentsia, and at this time he became involved with the Green Lantern, the literary circle that was part of the radical secret societies that would eventually lead to the Decembrist Uprising. The ideas he encountered in these circles soon found expression in his verse, drawing the ire of the authorities, and Pushkin was transferred from the capital in 1820, just before the publication of his first epic poem, Ruslan and Lyudmilla.

Between 1820 and 1824, Pushkin travelled extensively through the southern reaches of the Russian Empire, spending time in the Caucasus, Crimea, Chișinău and Odessa. Strongly influenced by Byron in this period, Pushkin was an ardent supporter of Greek Independence, and his Romantic idealism saw expression in two celebrated narrative poems, The Captive of the Caucasus (1821) and The Fountain of Bakhchisaray (1824), which he wrote alongside reams of love poetry that include some of the most famous lyrics in the Russian language. He also began, in 1823, to write what is probably his preeminent work, the novel-in-verse Evgeniy Onegin. The intricate descriptions of Petersburg society and fashionable life in the first chapter, despite the jaded protagonist's disdain for them, are an ironic expression of Pushkin's own homesickness for the capital.

Prey to the increasingly illiberal environment at the end of Alexander I's reign and the nervous authority of local governors, Pushkin was placed under even further confinement at the family estate of Mikhailovskoye in Pskov Province from 1824 until 1826. Here he continued to work on Evegeniy Onegin and produced his first major dramatic work, the tragedy Boris Godunov (1825). By the time of the Decembrist Revolt in 1825, Pushkin had little direct contact with the participants, but copies of his poems found among their personal effects would later further damage his reputation in the eyes of the authorities.

A personal audience with the new Tsar, Nicholas I, in Moscow in the autumn of 1826 secured Pushkin liberty of movement and, theoretically, the personal protection of the highest power in the land, with Nicholas undertaking to be the poet's only censor in future. Extraordinarily enough, Nicholas kept his word, and personally edited much of Pushkin's subsequent work prior to publication. This uneasy combination of patronage and restriction (augmented by periodical attacks on Pushkin's works by critics employed by the Third Section, the secret police established to monitor dissent in the aftermath of the Decembrist Revolt) set a template for the Tsarist - and later Soviet - state's attempts to co-opt and manipulate its most talented artists.

Nonetheless, this meeting with the Tsar had a mollifying effect on Pushkin's attitude to power and the state, bolstering his burgeoning interest in Russian history, particularly in the reign of Peter the Great, which inspired works such as his narrative poem Poltava (1829) and the unfinished novel Peter the Great's Negro (1828), his first attempt at a long-form prose work, telling a fictionalized version of his great-grandfather's life.

In December 1828 in Moscow, Pushkin first met his future wife, Natalia Goncharova. Then at the age of sixteen, Goncharova was already a celebrated beauty in Moscow society, and Pushkin later admitted that he fell in love at their first meeting. His suit was initially rejected by Goncharova's mother, who was concerned by Pushkin's libertine reputation, his debts, and his conflict with the authorities, as well as her daughter's youth, and Pushkin tried to overcome his disappointment by travelling again to the Caucasus in 1829, to visit officers in the Russian army fighting the Turks.

Returning to Moscow the following year, Pushkin again approached Goncharova's mother, and this time she agreed to his proposal. Before the wedding, Pushkin's father presented the poet with his estate at Boldino in Nizhny Novgorod Province. Due to an outbreak of cholera, Pushkin found himself caught there in the autumn of 1830 for three months, and it proved to be the single most productive creative period of his life, producing the final chapters of Evegniy Onegin, Pushkin's first published prose collection The Belkin Tales, the compilation of dramatic pieces known as The Little Tragedies, the fairytale The Tale of the Priest and his Workman Balda, the comic poem The Little House in Kolomna, and a considerable quantity of shorter verse.

Pushkin and Goncharova eventually married in Moscow on 18 February 1831. They set up home in Moscow in a rented apartment on Ulitsa Arbat (now a memorial museum), but only three months later, frustrated by his mother-in-law's interference in their domestic life, Pushkin moved with his young wife back to Tsarskoye Selo for the summer and then to St. Petersburg.

Pushkin would spend most of the last six years of his life in St. Petersburg. However, neither his new marriage nor his return to the capital were to bring the poet much joy. He returned to government service, initially working as a historiographer in government archives, which was the state's method of supporting his plan to write about the reign of Peter the Great. The November Uprising against Russian rule in Poland of 1830 and the Cholera Riots in various Russian cities including St. Petersburg in 1830-31 both briefly convinced Pushkin of the need for strong leadership to protect the Russian state, and this was reflected in his poetry of the time, causing a rift with some of his liberal readers.

Gradually, however, Pushkin's antipathy to authority reasserted itself. Despite the public's lukewarm reception of The Belkin Tales, Pushkin continued in his efforts to write long-form prose, and the subjects he was drawn to were anti-authoritarian figures such as the Robin Hood-like dispossessed landowner of his incomplete novel Dubrovsky or the Cossack pretender Yemelyan Pugachev, whose rebellion in the reign of Catherine the Great was the subject of Pushkin's History of Pugachev (1834) and the backdrop to his novel The Captain's Daughter (1836).

Pushkin was appointed a member of the Russian Academy in January 1833. However, his popularity with the reading public, enamoured of the Romantic lyricism of his twenties and as yet uninterested in his experiments in prose, had suffered. Pushkin's meager income, meanwhile, was forced to cope both with the demands of a growing family (Natalia Pushkina gave birth to two daughters and two sons between 1832 and 1836) and with the increased expenditure entailed by life at the Imperial court (in late 1833, the Tsar named Pushkin a Kammerjunker, the lowliest of ranks, which the poet saw as a demeaning method to ensure his beautiful wife's presence at court functions).

The Bronze Horseman, arguably Pushkin's finest poetic work, was completed late 1833. It was archetypal for Russian literature both in its theme of an ordinary man buffeted and tormented by the immutable forces of heavenly and earthly powers, and in its depiction of St. Petersburg as a city of inhuman, even malevolent, grandeur and beauty. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was rejected for publication by the Tsar, and only printed in censored form after Pushkin's death.

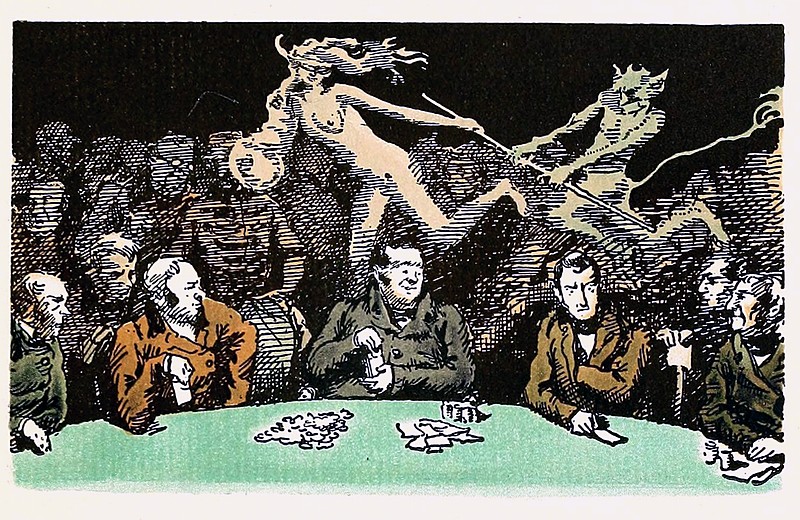

His renowned short story, The Queen of Spades, written at around the same time, was one of the few unmitigated public successes of Pushkin's later years, published in early 1834 in the new populist journal Biblioteka dlya chteniya. Collections of his poetry and prose works published later in the year were met with little enthusiasm. In a further effort to find a solution to his financial woes, Pushkin attempted to extricate himself from government service and move with his family to the country, but this was forbidden by the Tsar.

Part of Pushkin's reason for wishing to leave St. Petersburg and get away from the capital's social life may also have been jealousy. The truth of the events leading up to Pushkin's fatal duel is shrouded in layers of obfuscation that owe as much to scurrilous society gossip of the time as to the persistent temptation in later accounts to sentimentalize the life of a great poet. The tendency has been to paint Natalya Pushkina as a feckless beauty and Pushkin as a tormented genius riven by monstrous jealousy. Rumour made persistent claims that Natalya Pushkina was unfaithful, even suggesting that she was the mistress of the Tsar himself.

In 1835, she made the acquaintance of Georges d'Anthès, a handsome French cavalry officer serving in the Knights Guards of the Russian Empress. D'Anthès, having left France after the July Revolution, was adopted as a son by the Dutch plenipotentiary to the Russian Imperial Court, Baron Jacob van Heeckeren (there is fair reason to assume that Heeckeren's affection for D'Anthès was more than paternal). D'Anthès' attentions to Natalya Pushkina fueled gossip, the particularly malicious character of which may have been prompted by Pushkin's ill-concealed disdain for fashionable society and court life. In November 1836, Pushkin and several of his friends received in the post an anonymous pasquinade (a satirical letter) granting Pushkin a "Cuckold's Diploma". Pushkin was convinced that Heeckeren was the author, and challenged D'Anthès to a duel (as a diplomat, Heeckeren was not permitted to take part in duels himself).

One week later, D'Anthès proposed to Natalya Pushkina's sister, Ekaterina Goncharova, Pushkin's challenge was annulled, and the couple were married in January 1837. Although they were now brothers-in-law, Pushkin's animosity towards D'Anthès was not assuaged, and was further exacerbated as his family situation became the subject of more and more gossip and jokes. Pushkin refused to associate with D'Anthès, and brought the situation to a head on 26 January 1837 by sending an extremely offensive letter to Heeckeren, the only response to which could be a reciprocal challenge to duel.

The duel between D'Anthès and Pushkin took place the next morning to the north of St. Petersburg near Chernaya Rechka. As a result, D'Anthès was lightly wounded in his right arm, and Pushkin, shot in the stomach, was carried to his deathbed. He died in his apartments at 12, Naberezhnaya Reki Moyki (now the Alexander Pushkin Memorial Museum and Apartment two days later on 29 January 1837, having received assurance from Nicholas I that his family would be looked after.

Despite undertaking to provide financially for Pushkin's family and granting the poet his "forgiveness", the Tsar was seriously concerned that Pushkin's funeral would cause a public disturbance. The poet's funeral was announced as to be held in St. Isaac's Cathedral, but was secretly transferred to the church of the Imperial Stables, a few paces from Pushkin's apartments, on the night of 31 January. There was a heavy police presence, and only Pushkin's closest friends and a few foreign diplomats were in attendance. His body was then taken to Pskov Province, and buried at the Svyatogorsk Holy Assumption Monastery.

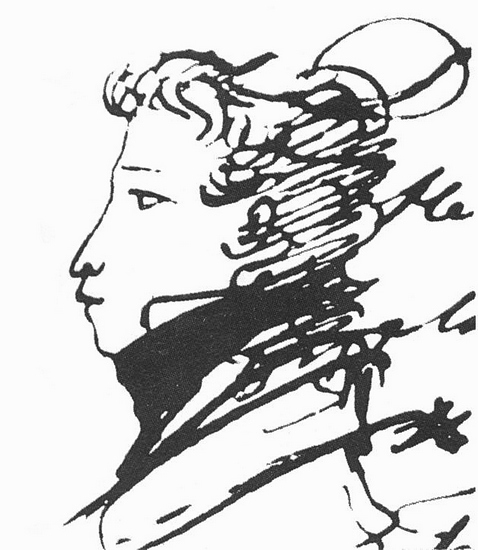

Although he was denied the chance to fully develop as a prose writer, Pushkin's tragic death was the final ingredient required to form an instant and immortal legend. Alongside the unquestionable mastery of his mature poetry, there is so much more that makes him a uniquely adorable literary figure: his distinctive features and the charming line drawings that decorated his manuscripts; the sheer scope of his verse, from beloved fairytales to the jokey erotic poems that he shared with the close friends of his youth; his carelessly noble involvement with radical politics; the endless academic guessing game played to identify the subjects of his most famous love lyrics; the exuberance and sincere kindness evident in his personal correspondence; the fond remembrance of nearly all who met him.

In all this and more, Pushkin was instrumental in making Russia a culture that loves its poets quite as much as their poetry. His legacy extends far beyond literature, his works providing the inspiration for numerous ballets and operas, among them Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov and Tchaikovsky's Queen of Spades, and even Miloš Forman's Oscar-winning movie Amadeus. Finally, despite his at times ambiguous attitude to the city, his imprint on St. Petersburg is immense, his name given to streets, metro stations, theatres and, of course, the charming town of Pushkin. The key locations of his life and death are marked with plaques and monuments, with an obelisk marking the spot on Komendantskiy Prospekt where he was shot, and in the very centre of the city on Ploshchad Iskusstv in front of the State Russian Museum, a huge statue of the poet erected to mark the 250th anniversary of the founding of the city. Fresh flowers laid almost daily at the foot of the monument by members of the public further attest to the reverence in which Pushkin is held to this day.