St. Petersburg (Petrograd) under Lenin: The Civil War and its aftermath (1918-1924)

Lenin may have become the ruler of Russia and Petrograd the first socialist capital, but a successful revolution here did not mean that the rest of the country had obediently followed suit. There were still vast territories that did not recognize Bolshevik rule. Although Lenin quickly negotiated a devastating separate peace with Germany which resulted in the loss of enormous tracts of land, the country itself erupted into brutal Civil War as Tsarist forces clashed with Red Guards. In this perilous situation, Russia's capital was, after a two hundred year interlude on the Neva, returned to Moscow, a greater distance from the insecure border, in March 1918.

Petrograd experienced mass exodus. The government bureaucracy with its attendant hordes of ministers, clerks, and military personnel relocated to Moscow, able-bodied men were embroiled in the Civil War, and civilians absconded to the countryside where food was easier to procure. Likewise, the wealthy and aristocratic, a targeted class under the new regime of workers and peasants, fled to safer grounds. Vladimir Nabokov, who had spent his childhood in a luxurious mansion within the shadow of St. Isaac's Cathedral, escaped on the last ship out of Sebastopol. Rasputin's aristocratic murderer Felix Yusupov - jewels and two Rembrandts in hand - was part of the royal entourage that crammed onto a warship in Yalta, kindly provided by the British for the Tsar's mother. Those who remained often ended up corpses: four Grand Dukes, including the Tsar's uncle, were shot in the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1918. As a result of this turmoil, in four years the population of the city was reduced by more than two-thirds, sinking from 2,400,000 in 1916 to 740,000 in 1920.

Meanwhile, the battle for political education was also under way. Geographical signposts were used to educate the populace in the ideas and ideals of the new regime and to eliminate associations with St. Petersburg's imperial and religious past. As it was clearly impossible for a self-respecting socialist city to have one of its main waterways named in honour of Catherine the Great, the Ekaterinsky Canal was renamed Canal Griboedova in 1923, after the nineteenth century aristocratic author and diplomat who Soviet historians rather improbably deemed an honorary Marxist.

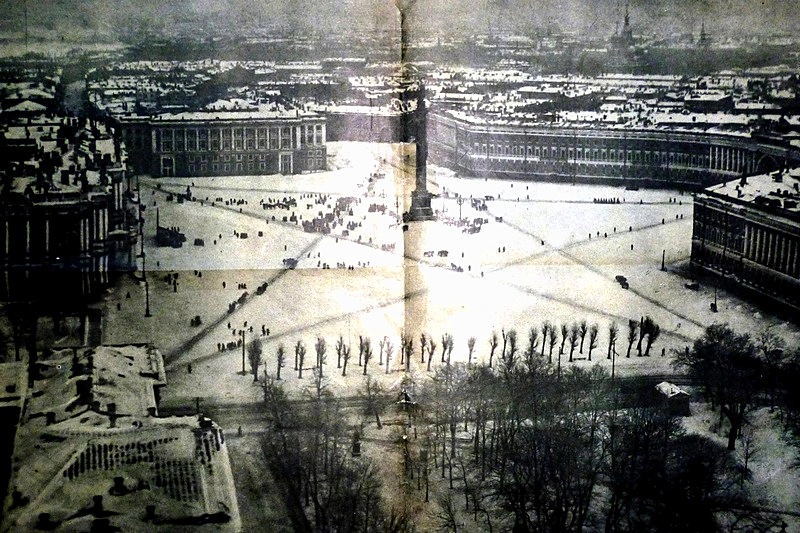

Street names with religious overtones were likewise deemed inappropriate by the atheistic government. Thus, the square in front of the Moscow Railway Station, previously called Znamenskaya Ploshchad after the nearby Church of Our Lady of the Sign (Znamenskaya Tserkov ), was renamed Ploshchad Vosstaniya ("Uprising Square") to commemorate the numerous revolutionary protests that had occurred here (the church itself was torn down in 1940, a fate which befell many churches throughout the land). In 1918, the city's grand central avenue, Nevsky Prospekt, was rechristened Ulitsa Proletkulta after the Organization of Proletarian Culture and Enlightenment, a short-lived experimental artistic institution (the Soviet passion for snappy portmanteau abbreviations quickly came to dominate not only the official language of the era, but also the toponymy of Russia's cities). In the same year, the Winter Palace, former residence of the Tsars, was renamed Palace of the Arts, and Palace Square became Ploshchad Uritskogo ("Uritsky Square").

But who was Uritsky? The story of this man is telling for the times. A Bolshevik revolutionary, Moisey Uritsky became head of the Petrograd Commune Commissariat for Internal Affairs and the Extra-Ordinary Commission - in other words, the infamous Cheka. This organization, which aimed at eliminating even the weakest or even non-existent opposition to the new social order through brutal terror, was founded in Petrograd within weeks of the revolution, with headquarters at 6, Palace Square in the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Here Uritsky coordinated the pursuit, prosecution, and execution of monarchists, military personnel, clerics, and others who opposed the Bolshevik regime. And here, on 30 August 1918, he was assassinated by a young military cadet in retaliation for the execution of several officers.

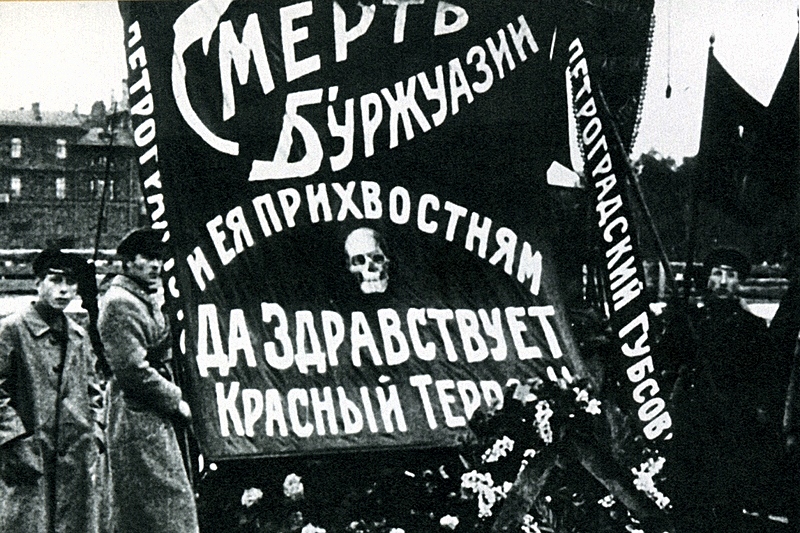

This event, along with an attempted assassination on Lenin, served as the pretext for the Red Terror, a wave of mass killings, torture, and repression that targeted anyone who dared to criticize the new regime, in particular the bourgeois and the nobility. By 15 October, when the Red Terror officially ended, 800 alleged enemies had been shot in Petrograd alone and more than 6,000 imprisoned. But the unofficial Terror continued on until the end of the bloody, tumultuous Civil War in 1921 when the Bolsheviks finally emerged victorious over those forces loyal to the ancien regime.