Peter Simon Pallas

Zoologist, polymath

Born: Berlin- 22 September 1741

Died: 8 September 1811

He then travelled in England and Holland to examine the countries' natural history collections, and in 1766 published his first scientific works in the Hague. He developed a new system for the classification of animals, based on his theory of historic development in the natural world and his idea that organisms could be represented like a family tree, showing sequential relations among the different taxonomic groups. Praised for its elegance and accuracy by his contemporaries, Pallas's system was later further validated with the acceptance of the theory of evolution. He achieved widespread fame among European scientists, and was made a member of the Royal Society and the Accademia dei Lincei.

Pallas was appointed professor of natural history at the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, arriving in the city in 1767. At the time, Catherine the Great, interested in learning more about her empire - its geography, natural history, peoples and resources - was arranging expeditions by brigades of scientists to survey the lengths of the lands she ruled. For the next six years, Pallas led an expedition that travelled first down the Volga River to Samara, then across the Urals into Siberia. Having visited Altai, the upper Amur region, and crossed the ice of Lake Baikal, he arrived at the end of 1772 in the town of Kyakhta, on the Mongolian border. Throughout the journey, he sent regular reports back to St. Petersburg, chronicling his observations in the fields of zoology and botany, as well as mineralogy, geology, and ethnography.

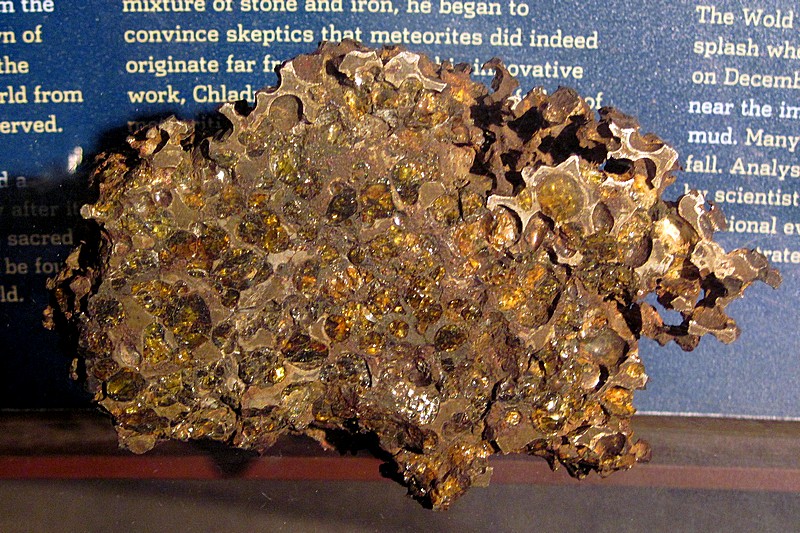

Pallas eventually arrived back in St. Petersburg in July 1774. He had discovered and described scores of new species of plants and animals, among them species that would soon become extinct as the Siberian wilderness was invaded by man. The wealth of materials collected in the six-year journey massively expanded the collections of the Kunstammer and many samples are still displayed there and in the various museums of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Among the most impressive is a 600kg lump of metallic rock found near Krasnoyarsk, later identified as part of a rare type of meteorite that was given the classification "pallasite".

Back in St. Petersburg, Pallas continued to sort through the materials he had collected, publishing several books in different fields, including ethnography and geography. He began work on his Flora Rossica, a comprehensive botanical survey of Russia of which, due to financial limitations, only two volumes were published. He also became close to Catherine the Great, for whom he helped carry out a peculiar research project to try to establish the truth of the theory of a single language as the basis of all languages in the world. To this end, an attempt was made to record different words in languages of the Russian Empire and throughout the world by sending out a survey (in the USA, George Washington instructed state governors to help the Russian Empress in her research). The result was published as a dictionary of simple terms in over 200 languages. Although methodologically flawed, this experiment, and especially criticism of its techniques, did much to develop a basis for the study of linguistics. Catherine also asked Pallas to teach her grandsons, Grand Dukes Konstantin and Alexander (the future Alexander I) natural history.

In the 1790s, Pallas embarked on further expeditions, travelling through the south of Russia, the Caucasus and Ukraine, where he studied the climate. In 1796, he settled on the estate granted to him by Catherine the Great at Shulyu, near Simferopol. During the final years of his life, he worked on his Zoographica rossi-asiatica, a comprehensive survey of the known fauna of Russia in three volumes. Although the work was completed in 1806, publication was delayed due to problems with the illustrator Christian Geissler, who had returned to Germany. In an effort to speed up Geissler's work, Pallas asked permission to travel to Berlin in 1810, where he died the following year. His zoological masterpiece was eventually printed almost two decades later, but remained the chief reference work for Russian zoology well into the 20th century.

As well as to meteorites, Pallas's name was given to several of the birds and mammals he described, as well as numerous species of plant, a volcano on the Kuril Islands and a mountain in the southern Urals, streets in Volgograd, Novosibirsk and Berlin, a peninsula in the Kara Sea, and the town of Pallasovka in Volgograd Region. Of the many German scientists invited to Russia during the enlightened reign of Catherine the Great, Pallas undoubtedly did the most to advance the scientific understanding of the vast lands of the Russian Empire.